(Photo Credit: Point of View)

(Photo Credit: Point of View)

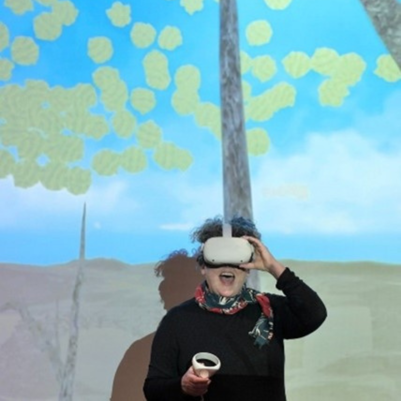

In mid-February, I had the privilege of speaking at the School of Digital Arts (SODA) at Manchester Metropolitan University alongside a panel of researchers interested in exploring audio-visual interfaces and their potential impact on wellbeing. Dr. Adinda van ’t Klooster, an artist and the event’s organiser, is an interface developer who created the AudioVirtualizer (2019) and the voice-controlled VRoar (2023); both offer captivating aesthetic interactive experiences with significant potential for enhancing well-being and vocal training.

The incorporation of VR technology into artistic endeavours is not a recent development. Over the past decade, notable examples like Björk's "Stonemilker" from the album Vulnicura have showcased immersive 360-degree VR experiences on platforms like YouTube. By leveraging VR, viewers can navigate the environment the video is filmed in simply by manipulating their mouse or using a touch screen on a tablet. By 2016, an array of music artists began experimenting with VR technology to enhance their artistic expressions.

Educational institutions have also embraced VR for innovative pedagogical purposes in recent years. For instance, a metaverse school has interconnected 84 schools across 24 countries, integrating VR into various academic subjects. Students explored anatomy by traversing virtual representations of the human body. Just imagine the prospects for anatomy classes in a vocal pedagogy class! Other educational institutions in the United States, like the University of Iowa, have utilised VR as a dynamic tool for performance, fostering interdisciplinary collaboration between faculties in computer science, theatre, and art. In the United Kingdom, the Royal College of Music (RCM) has pioneered a cutting-edge Performance Simulator, enabling musicians to engage with virtual audiences and even introducing disruptive elements to cultivate resilience and adaptability.

According to a report by Research and Markets (2022), online music education stands out for its ability to enhance interactivity, creating immersive learning environments by integrating videos, audio, and graphics. The anticipated Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) in online music teaching from 2020 to 2027 is an impressive 18.4%, surpassing the average global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate. However, there remains a significant knowledge gap regarding the utilisation and awareness of the benefits of online music education, particularly in developing nations. Nonetheless, the introduction of Virtual Reality (VR) holds promise for further enriching the learning experience.

Today, bringing VR technology into the 1:1 voice studio is made possible with devices like the Quest VR headset. Of course, online sessions rely on your client having access to such a device. Applications like Ovation offer virtual audience settings, enabling users to refine public speaking skills in customisable scenarios, from managing hecklers to gauging applause. Whether you prefer singing in a private room or a concert hall, Sing Together provides a karaoke experience. For those seeking to improve accompaniment skills, there are training tools such as Piano Vision to support you, and you can play with touch control synthesisers and samplers using Virtuoso. Moreover, singing instructors specialising in helping individuals cope with performance anxiety might find interest in utilising meditation apps featuring calming soundtracks, potentially fostering overall well-being through VR immersion.

Interest in using VR as a therapeutic tool is increasing; for example, combining VR and singing (Tamplin, J. et al. 2020). Although VR has shown potential as a tool for developing emotion regulation strategies, it is essential to acknowledge that further research is needed to understand its efficacy fully (Zeng et al., 2017; Chaabane et al., 2022). Additionally, the effectiveness of VR tools depends upon how receptive an individual is to the technology (Slater & Sanchez Vivez, 2016; Servotte et al., 2020). Despite calls advocating for a reduction in screen time (Muacevic & Adler, 2022), there is an emerging perspective that exergaming activities, which integrate digital gaming with physical activity, could offer a promising approach to offsetting sedentary behaviours (Benzing & Schmidt, 2018). Admittedly, the notion might appear paradoxical, and the irony is not lost on me.

I have so many questions, but for today, I will leave pondering:

- Could an audio interface be a valuable training aid in the 1:1 studio?

- As performers increasingly embrace technology in their practice, should we explore how these advancements can aid in preventing vocal issues and facilitating rehabilitation?

- And how might integrating such technologies into training and rehabilitation impact performers’ overall well-being?

Do you have a VR headset? We would love to know if you already use this technology in your studio or teaching space. You can email us at info@voicestudycentre and let us know.

References:

Benzing, V., and Schmidt, M. (2018) “Exergaming for Children and Adolescents: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats,” J Clin Med, 8;7(11):422. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm7110422. PMID: 30413016; PMCID: PMC6262613.

Research and Markets. (2022) https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2022/02/16/2386048/28124/en/Outlook-on-the-Online-Music-Education-Global-Market-to-2027-Featuring-Moosiko-Skoove-and-Tonara-Among-Others.html.

Chaabane, S., Etienne, A-M., Schyns, M., and Wagener, A. (2022) “The Impact of Virtual Reality Exposure on Stress Level and Sense of Competence in Ambulance Workers,” Journal of traumatic stress, 35(1), pp. 120–127. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22690.

IOWA Now. (2024) UI makes immersive virtual theater a reality. Available at: https://now.uiowa.edu/news/2018/12/ui-makes-immersive-virtual-theater-reality (Accessed 23 February 2024).

Nakshine, V. S., Thute, P., Khatib, M. N., and Sarkar, B. (2022) “Increased Screen Time as a Cause of Declining Physical, Psychological Health, and Sleep Patterns: A Literary Review”, Cureus, 8;14(10):e30051. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.30051.

Royal College of Music, London. (2024) Groundbreaking Performance Laboratory unveiled at the Royal College of Music. Available at: https://www.rcm.ac.uk/about/news/all/2023-01-22performancelaboratory.aspx (Accessed 23 February 2024).

Slater, M., and Sanchez-Vives, M. V. (2016) “Enhancing our lives with immersive virtual reality,” Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 3(74), 1–47. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2016.00074.

Servotte, J.-C., Goosse, M., Campbell, S. H., Dardenne, N., Pilote, B., Simoneau, I. L., Guillaume, M., Bragard, I., and Ghuysen, A. (2020) “Virtual reality experience: Immersion, sense of presence, and cybersickness,” Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 38, 35–43. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2019.09.006.

Tamplin, J. et al. (2020) “Development and feasibility testing of an online virtual reality platform for delivering therapeutic group singing interventions for people living with spinal cord injury”, Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 26(6), pp. 365–375. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X19828463.

Zeng, N., Pope, Z., Lee, J. E., and Gao, Z. (2017) “A systematic review of active video games on rehabilitative outcomes among older patients,” J Sport Health Sci. 2017 6(1):33-43. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2016.12.002.